The Unbearable Lightness of Working as a Stylist: Composing Space, Composing Self

Some of you may know that for the last several years, my income has come from my work as a set, prop, and wardrobe stylist in the commercial photo and video world. While “wardrobe stylist” or “costumer” are terms that aren’t too foreign to most people, set and prop styling are slightly more nebulous terms.

But here’s the easiest summary of what I do: on a shoot, I’m in charge of choosing and arranging everything in the camera’s frame that isn’t a person. For a scene of a man and wife eating a meal in their home kitchen, a prop stylist is the person who brings the dishes and arranges them in the camera frame just so. A set stylist, on the other hand, will do the same for the table and chairs, the curtains on the window, the olive tree standing in the corner. 99% of shoots I’ve been on, I’m doing both, emperor of a small kingdom of inanimate subjects.

Is an actor holding a fork? I decide which one has the right color, weight, and silhouette. Are there drapes on that window? I’ve chosen them, and I’ve also opened them to just the right interval of space.

It's still kind of incredible to me, seven years into this work, that I make money doing what I do. And yet, it turns out that a knack for composing space in pleasing and functional ways, or an ability to make strategic and aesthetic decisions between near infinite variations on possible objects that a client needs to situate inside a camera’s frame, is a quality that most people seem to lack. And so long as this should be true, I continue to be paid for my taste.

Maybe it’s

1. the seemingly insubstantial nature and fraudulent feeling of my job,

2. my persistent curiosity about the ineffable skillset which I ply

3. the apparent absence of these proficiencies in the general population

that has led me to reflect on what styling actually means, what a stylist does, and to the deeper nature of the still lives—as small as a tabletop, as wide as a soundstage—that I’m charged with creating. But I think my curiosity comes just as much from the fact that styling and—let’s say it, decorating—space are acts which have largely escaped real theorization.

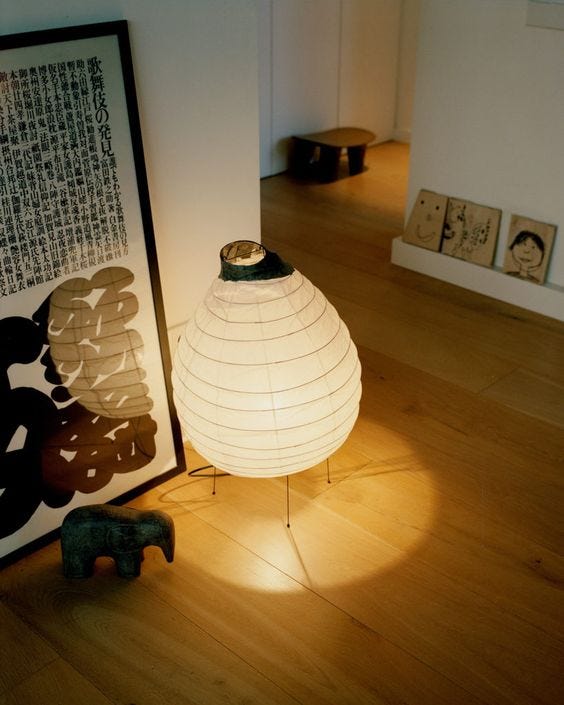

Take any interior design book, for example. You won’t likely find criteria of any real depth for what makes a space or an arrangement “successful.” Likewise, descriptions of how a space operates and the nature of its total effect on the viewer don’t tend to stray beyond formal descriptions of what we’re looking at (a “blue herringbone banquet” or “a Noguchi rice paper lamp”), the social aspirations or tastes of a given subject, and dramatizations of the way that the space is used or how the eye moves around it. On the other hand, the world of architectural theory pays little to no mind to the question—let alone the politics—of choosing what decor enters or exits the frame of architectural photography. Interior design studies, meanwhile, are still emergent and in search of their identity.

This is why, in a small English-language bookshop in Nice this Summer, I was so excited to come across a book I’d been dying to get my hands since I caught wind of its coming publication—Emanuele Coccia’s Philosophy of the Home: Domestic Space and Happiness (2024). Philosophy, he contends, has also very seldomly concerned itself with the domestic sphere. You’d almost be forgiven for concluding that the major voices of European philosophy lived only in the streets of European cities, large and small, for all the scant attention they pay to the home, or to the matter of decorating it. While we’re at it, let us also praise Coccia’s forebearer, the great Gaston Bachelard, another Parisian philosopher whose seminal text The Poetics of Space (1958) serves as a clear predecessor to Happiness.

As it has apparently been true of the world of philosophy, on sets, no one has the time, or frankly the need, to interrogate the deeper impulses which shape how we are drawn to certain arrangements of objects in space over any number of infinitesimal variations. By necessity (time is money), we stick to an improvised shorthand when a director and I are working together to land at the right “look.”

If we feel moved to explain our preferences, phrases like “it feels off” or “it doesn’t work” more or less mark the outer limit of our theorizing—language we use to communicate gut instincts (or VIBES, a word I’m now ready to retire). I think these instincts are likely not really instincts at all, but rather a rather rational, mundane process which has lost its language. A lifetime of image consumption has equipped us with an unconscious standard against which we judge our current compositional efforts. But without the time or space to retrieve any trace of our conscious memory of them, these image references have dissolved into a language of endorphin releases, a clench of the stomach, a tension in the shoulders. Our socialization to decorative norms has, in other words, been transposed into echoes whose source is obscured in shadow.

And so, when a composition elicits a feeling of displeasure or unease—the aforementioned “off”-ness—we have all we the motivation we require to create a different arrangement. If the vibe in our gut feels good—the composition therefore is good.

And because we are all socialized similarly, those of us on set can often merge minds and understand—or at least, unconsciously sympathize with—all that may hide in the shadows behind an order to “move the vase to the right”. At least we think we do—but we’ve never had to test it or challenge ourselves to draw it out into conversation longer than thirty seconds. We don’t ask what these instincts are, or where they come from, or how they function. And when we do, we rely upon the same linguistic shortcuts that ultimately foreclose any possibility of arriving at the truth.*

Now, I’m not saying a set is the place to conduct a much-needed theorization of the still life, or of the domestic interior, real or staged. But I have found myself asking over the years: what other forces govern our instincts around composing space, around domestic decoration? Doesn’t it feel like there is more going on beneath the surface, when we decide what “works” and what doesn’t, beyond the imitation of other images of other desirable spaces?

We might turn to some form of evolutionary science or psychology for answers. There are likely mathematical answers to why certain compositions enchant us while others leave us frustrated, probably rooted in geometric patterns in nature, recurring rules of harmony and proportion. We could also further draw on a logic of psychological metaphor, which, come to think of it, is basically the system of metaphors which governs feng shui (e.g. in the bedroom, feng shui principles would have you place your shared bed in the middle of the wall to promote balance and equality in your relationship, and to avoid placing items under your bed because they will clutter and infect your mind).**

But both of these approaches strike me as ultimately inadequate to the question. To say that certain formal rules of arrangement are always more pleasing to us than others would lead to a purely psychological framework, one which ultimately dead ends into a nice and tidy cul-de-sac of biological determinism (“We’re just animals, after all!”). But my own reptilian instinct tells me there is more than evolutionary drivers influencing our predilections for certain compositions over others. I mean, duh—how could there not be?***

These are pet concerns for me as a professional stylist. But they strike me as questions we might as well all ask ourselves since we are all now stylists: after all, in our homes, in our social media photography, we are all engaged in decorative decisions every day.

Here is a long sentence, along with a key part of my working theory. When we have license to “style” the world around us—that is, to decide what is in our frame of vision (and others’) and to arrange it to our liking, whatever that liking may be—we want, in this totally separate, sovereign set of objects, to create a portrait of ourselves. We are not, however, Narcissus on the riverbank, gazing at our own reflection. After all, a line of antique drinking glasses on a marble shelf does not appear (in any formal sense) identical to our own reflection.

While we love and loathe (in any case, are entranced by) our own reflections, unlike Narcissus, as we move through the world, we throw mirrors at the world before us, mirrors which reflect us but do not image us directly. In essence, when we arrange objects in space—which usually happens in the private sphere of the home or for the mobile stage we unfold before our roving iPhone camera— we seek not a visual replica of ourselves but a proxy self, a miniature theater which contains a human essence or quality we hope to absorb into ourselves.

This is the melancholy and ecstatic longing which underlies all of the work of one who styles, whether we’re aware of it or not. It is the soft, mossy floor from which all our endeavors grow. The job of a stylist is to understand that, at the heart of all interior decoration, there lies this strange desire for self-recognition in objects, and perhaps a longing to become more object-like oneself.

I never expected my years of arranging things to grant me any insights into human desire, or that mulling over the order of books on a shelf or the angle of a teacup would lead me to any conclusions about the impulses which underlie our relationships with objects and spaces. Life on a set is about as far from intellectual as you can get. But intuiting that there is a pervasive, natural, recurring desire to upend the bounds between our bodies and ordinary domestic objects and spaces has led me to all kinds of far-flung, galaxy-brained thoughts about freedom and oppression, self-actualization and self-constraint, and the daily limits to self-knowledge.

But much, much more on all that to come.

See you next month,

Chris

Endnotes

*Fashion is also a particularly awful arena for the suffocatingly literal-minded metaphors which characterize much of the discourse, as it exists, in interior design—e.g. "women are wearing jackets with military lapels because they are armoring themselves against the precarity of the economy,” etc. etc.

**Chapter 9 of Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space (“The Dialectics of Outside and Inside”) is a difficult but formidable expression of how language conditions thought. Using the terms of “inside” and “outside,” he makes a fascinatingly argued case for why each of us should remain vigilant about which metaphors we tend to reach for when attempting to describe the world and our experience, and how a reckless deployment of such spatial distinctions like “inside” and “outside” conditions our knowledge of the world and blinds us to the fullness of reality. Really great stuff.

***Like Gaston Bachelard, I tend toward phenomenology as a fruitful methodology for understanding our tastes—I’ll certainly get into that more in a future essay.

Recommended Reading

Emanuele Coccia, Philosophy of the Home: Domestic Space and Happiness (2024)

Gaston Bachelard, “The Dialectics of Outside and Inside,” from The Poetics of Space (1958)

Image Credits

Image 1: Weekend Creative, from this blog post

Image 2: Source unknown

Image 3: Salva Lopez for Monocle, as seen here

Image 4: Matthew Williams for Remodelista, as seen here in the home of designer Corrine Gilbert

Image 5: Source unknown